It is a project of extravagant dimensions and it has been blocked for almost 20 years by a protest of epic tenacity and occasional violence.

But this week, Italian plans for a 56-kilometre rail link under the Alps, four miles longer than the Channel tunnel and linking Turin to Lyons, will move into a new and possibly decisive phase.

Officials are due to expropriate a stretch of sloping grassland near the Alpine village of Chiomonte, outside Turin, where work will begin on Italy‘s side of the border. The first planned excavation is of an access tunnel to allow geologists to test conditions.

When the site was fenced off last summer, almost 400 people were injured in the resulting clashes between demonstrators and police. Twenty-six people accused of taking part in the violence have since been jailed.

The authorities have declared the site of national strategic interest and made it subject to the same legislation that applies to army barracks. But part of the land has been bought by the protest movement, and Lele Rizzo, a prominent figure on its more radical wing, said that when the expropriations begin “we shall try to be there, on our property.”

The first demonstration against the high-speed train (Treno Alta Velocità, TAV) route was in 1995. The resistance has continued ever since and, in February, almost claimed a life when an activist who climbed an electricity pylon fell after being severely burned.

Taken aback by the intensity of the protests, successive governments in Rome have havered and dallied. But Mario Monti‘s non-party government appears determined. It came into office in November charged with reanimating Italy’s moribund economy and, said Mario Virano, special commissioner for the tunnel, “infrastructure is considered as a mechanism for the creation of economic growth”.

Virano is charged with persuading local people and their representatives of TAV’s merits. Last month, he was summoned to Rome and was astonished to find on the other side of the table, in addition to Monti, no fewer than four members of his cabinet. According to Virano, at the end of a meeting lasting several hours, Monti declared: “We want to go ahead with [the TAV project], not because we inherited it but because we believe in it.”

So why does the scheme arouse such passionate feelings? All Alpine landscapes have a certain grandeur. But while the Susa valley contains important historical monuments and archaeological remains, it is not the prettiest.

Apart from the existing train line, it is dotted with quarries and factories. The land on which last year’s pitched battle was fought lies in the shadow of an array of monstrous concrete pillars that hold up part of the A32 motorway, built in the 1980s.

“That is the real abomination. Yet it was put up without any resistance,” said Renzo Pinard, the mayor of Chiomonte and one of only two local authority chiefs along the proposed TAV route who back it.

Environmentalists have said that the mountains through which the tunnel will be dug contain deposits of uranium and asbestos. Massimo Zucchetti, who lectures on nuclear engineering at the Polytechnic University of Turin, is an adviser to the Susa valley authority, whose president is a leading opponent of the scheme.

But even he says: “I don’t think that the uranium, nor even the asbestos, represents the main reason for not carrying out this project.” The hazards of digging out the minerals could be eliminated by the use of powerful extractor fans.

Nor is there a danger of lorries, heavy with rocks and dust, rumbling through the valley’s peaceful villages: it has been agreed the waste will be removed via the motorway. So what is the problem?

This is an odd conflict, in which the normal roles are reversed: it is the proponents of the scheme who are the dreamers (or visionaries, depending on your point of view). And it is the opponents, including a fair share of anarchists and environmentalists, who argue for financial necessity and fiscal prudence.

The two camps disagree over the project’s net, long-term balance of carbon emissions. But, said Rizzo: “While the No TAV movement began as an environmental protest, today – I have to say – it is the economic arguments that take priority. The tunnel would be an utter waste of public funds. The existing railway line could support any possible increase in traffic. The scheme continues to be based on projections made 20 years ago.”

A document produced by the government in support of the project counters that it will slash the journey time between Paris and Milan from seven hours to four, bring about “a significant increase in the volume of freight transport” and halve the cost of transporting goods by rail. It could also bring about “a notable reduction in the number of lorries on the roads in the delicate Alpine environment”.

But these and other assertions are impossible to test, because the Italian government has never published a cost-benefit analysis. Virano said his office had completed one, but was waiting for it to be formally unveiled in Rome by the appropriate minister.

He said that the outcome, using the European Union’s central macro-economic scenario, was environmentally “very positive” and financially “slightly positive”. But, say the tunnel’s proponents, projections based solely on today’s facts and figures miss the point: that “Italy’s Channel tunnel” is intended to create its own, new reality.

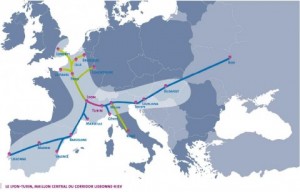

Virano points to the experience of Switzerland, which doubled its rail system traffic by excavating tunnels through the Alps. More importantly perhaps, TAV is fundamental to a vision of Europe conceived in Brussels, where Monti spent almost 10 years as an EU commissioner.

The Susa valley lies on a proposed rail corridor which, before the Portuguese pulled out, was intended to run from the Atlantic to Ukraine’s border. By linking Turin to Lyon, moreover, it would connect the two biggest cities in a region the Eurocrats have dubbed AlpMed.

Whether this region exists in any meaningful sense is debatable. On the Italian side, the A32 is all but deserted: a journey from the start to the last exit before the French border was shared with fewer than 20 vehicles.

But put these objections to Virano and he hands over a map that appears to show the main rail links in today’s Italy. In fact, it was drawn in 1846 by the Count of Cavour, one of the architects of Italian unification. “If Cavour had taken into account commercial relations between the various cities then he would never have put in these lines,” said Virano. “Some were in countries that were at war at the time.”

Engineering, in other words, can make dreams come true. And in this case, it may have to. Much of the work on the French side has already been done and, were Italy to pull out, say officials, it would face a huge bill for damages of at least €1billion (£820 million).